Ears to the Ground

Feature

Chris Watson, sound recordist, artist and composer, is Artist in Residence for Nature Unwrapped; Pascal Wyse introduces him.

The alarm sounds at 2:45am. Last night’s meal barely digested, we hit the road. It is an hour’s drive, and we need to reach Dryburn Moor, Northumberland, before the sun does. At the other end there is a 20-minute stumble in the dark, across pitted and uneven land, carrying sound recording equipment, including 200 metres of microphone cable. A dense and unpredicted fog is making anything beyond three metres slip into darkness, and the GPS seems very confused about where we are. Worse, the mist has subdued the birds – just lone and occasional curlews and grouse instead of a chorus against the sunrise. ‘That’s the problem with nature,’ says Chris Watson. ‘It doesn’t tend to read the script.’ For the wildlife sound recordist, one piece of kit you must pack is a sense of humour.

‘Sound is visceral, it connects to our hearts and imagination in a very direct way’

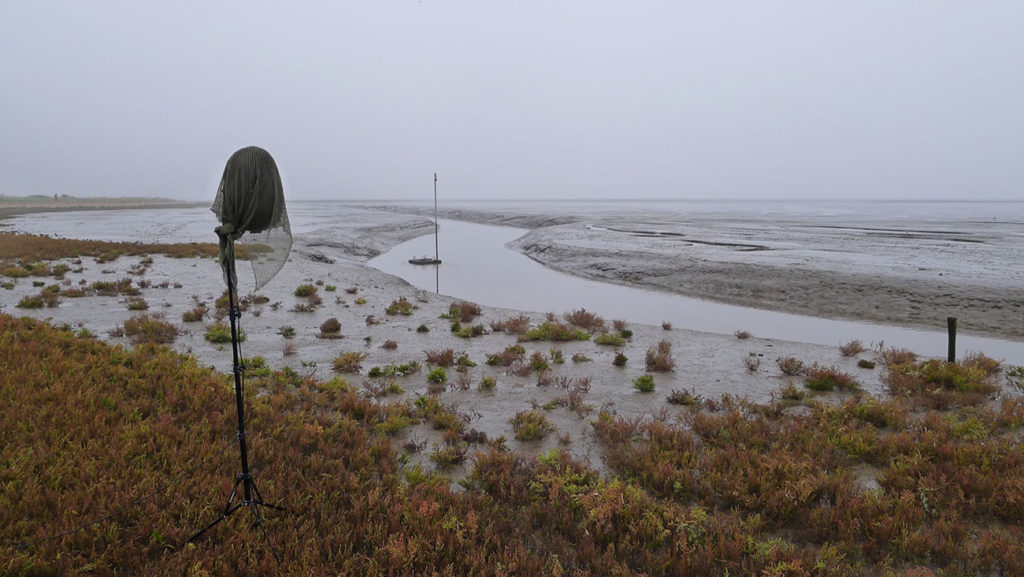

Anyone who has had the good fortune to go recording with Chris, or attend one of his workshops, will know that his deadpan humour rides alongside a dedication to his craft that is anything but frivolous. They will also know that listening to his recordings of the natural world can be, to borrow R Murray Schafer’s phrase, a truly ‘ear-cleaning’ experience. Across the year, as part of Nature Unwrapped, visitors to Kings Place will be able to listen to a range of natural European habitats and wildlife recorded by Chris. Month by month, these recordings will smuggle the seasons indoors, challenging the controlled environment of the concert halls: winter on The Wash, Norfolk, with wading birds and wildfowl… early spring on high heather moorland, with curlews, grouse, golden plovers… Insects and invertebrates in Devon… A red deer rut in the Highlands… The shifting ice of Vatnajökull in Iceland.

Live events include Chris sharing the stag with George Monbiot, in a conversation about landscape that will reveal how sound can diagnose the health of an ecology, as we hear the contrast between healthy and bleached coral reefs, or how the manipulation of moorland leaves behind little but the voices of lone skylarks. Along with performances with Lau (Martin Green, Aidan O’Rouke & Kris Drever), Chris will also install a piece comprised solely of recordings made under water, delivered in surround sound. ‘The oceans are significant in terms of climate,’ he says, ‘but they are also the most sound-rich habitat we have. We will travel from the Antarctic to the Arctic, all connected in sound.’

Chris’s own journey into sound goes from being a founder member of Sheffield’s experimental music group Cabaret Voltaire in the 1970s, becoming a sound recordist for many of the BBC’s flagship nature documentaries (often with David Attenborough, often winning awards), through to works that weave his recordings into arresting compositions. What you hear is a unique combination of technical diligence, fieldcraft and narrative instinct that goes way beyond the sum of those dry terms: we are taken ‘outside the circle of fire’, deep into the natural world, microphones staked out where our ears could never go.

‘We are taken deep in to the natural world, microphones staked out where our ears could never go’

Our hearing, says Chris, was once a matter of life and death. ‘40,000 years ago, when we were all living in caves, asleep at night, and a pack of spotted hyenas or a sabre-toothed tiger crept in… Well, we’ve evolved from those that heard those predators and managed to escape.’

As our city environment chokes up with noise, it becomes harder to hear, but even harder to engage with the more active – and rewarding – practice of listening. ‘We don’t have earlids. We block out the world with headphones, not always to listen to the music so much as shut out the noise pollution,’ notes Chris. ‘Giving people the opportunity to stop and actively listen can literally open their ears. You engage with the world in a different way. ‘With all the current discussions about what we are losing – habitats, or, in this country, individual species such as turtle doves and curlews – I think it’s important for everyone to reconnect with landscape. The seasonal element is also important: these are shifting sounds that evolve through the year, which is another idea we are in danger of losing in our air-conditioned lives.’

These recordings, though, don’t come explicitly freighted with a message. They don’t need to. ‘Sound is visceral, it connects to our hearts and imagination in a very direct way,’ says Chris. ‘I can listen to a recording I made twenty years ago and immediately remember where I was, how I felt. It harnesses that power of recall. By allowing people to hear these places, you’re not lecturing them, you’re just letting them realise the blindingly obvious: that they are significant.’

© Rosie Watson